To me: “Ready?”

Me: (brief hesitation), questioning “yes” in Spanish, then

affirmative “yes” in Guna!

This pretty much sums up my day-to-day experience in Guna

Yala this past week, but more specifically my personal adventure to the island

of Tigre.

Journal entry from April 11:

Yesterday I went to Tigre through a course of events I don’t

completely understand. I blame a lot on language barrier, but I also think a

lot has to do with the easy-going nature of people here and how normal it is to

rely on one another.

Sailar Iguayoikiler (The head authority and my host on

Nargana) kept telling me to get my things ready to go to Tigre as if I would be

staying there. We talked about it and I really felt much more comfortable not

staying the night. Yet a few hours later he would repeat his instructions to

pack a small bag and put together the rest of my stuff to leave behind.

Additionally, each new person I talked to about going to Tigre seemed to also

be under the impression that I would need to spend the night.

“Where would I spend the night?”

“Just ask around”

“Are there any boats coming back to Nargana later today?”

“Maybe” (this last part seemed to be said more to pacify me

rather than given as accurate information)

Great. I was feeling less and less sure about this trip. I

even toyed with the idea of just calling my trip off. But I also had to get off

the islands of Nargana and Corazon de Jesus to do more interviews and get more

perspectives on my research.

After some back and forth and quite frankly contradicting

conversations with the Sailar and a few other people, I figured out from where

and when the boat would be leaving. Of course it left about an hour later than

the latest time given to me, which was 1:00pm.

The day before was actually my intended day to go to the

island of Tigre with a man I had met the first time I was in Guna Yala. Martin

arrived at the Sailar’s house the morning we were to leave and informed me that

it would cost $36 to get to Tigre, “to pay for gas”. One gallon of gas here is

$6 and he said they would need 6 gallons. There were a couple things wrong with

this. 1. It cost me $20 to go from Carti to Nargana, which is at least 5 times

the distance from Nargana to Tigre, 2. It would not take 6 gallons to reach

Tigre. No deal, and the Sailar backed me up on this and seemed about as

frustrated as I was that someone would try to cheat me like that.

So on April 10, I left for the island of Tigre in a boat

full of delegates from Nargana and Corazon de Jesus. They were headed to an

island beyond Tigre for a meeting to discuss the increasing tourism and

problems associated with it, such as trash. I got to know a few of these

gentlemen while waiting for the boat to leave and while headed to Tigre, and I

must say I found them all incredibly welcoming and kind, as I have found most

people here that I have had conversations with. Of course as soon as I get to

know these people and feel comfortable, I am handed off to the next unknown

situation, in this case, the island of Tigre.

I am dropped off at the dock where the men say goodbye and a

few other words in Kuna. The only soul around is a disgruntled looking man who

immediately begins walking in one direction. Not sure who he is or where he is

going, but having no other “guide” besides, I follow him. I reason that maybe

the men in the boat had been telling him where I was to go.

Tigre is known for being a more traditional island, and I

could immediately feel the difference. The island was far calmer than Nargana,

with hardly anyone out and about. Most people seemed to be busy inside the

shady houses or off at work.

Not entirely trusting my “guide”, I stop at the entrance to

a few houses to say “Erasmos?” the contact I was given by Iguayoikiler. The

women continue pointing me in the direction of the hobbling man until he

finally stops, abruptly ending my guided tour (if that is indeed what he was

trying to do). I walk up to another home where a young woman immediately asks

if I want a mola. I smile and say no, and then give my contact’s name again. To

this the girl steps out and leads me to a compound at the tip of the island.

All this while the older women continued to look on with mild amusement at this

lost foreigner while the kids waved “hola” and the toddlers gawked in awe at my

towering white and alien presence. This combination of looks I came to know

very well in my brief time on the island. I stand out so horribly here as to

make one poor infant cry. On average I would say that the people here reach my

shoulders, the women even shorter.

I am dropped off with who I would come to learn is Erasmos’

wife, mother-in-law and two sister-in-laws. The first of these women informs me

this is Erasmos’ home and he is currently at his office, to where she

immediately gets up to take me. Back across and to the complete opposite side

of the island we go.

We reach a man working in the garden outside a white cement

building. I assume him to be Erasmos. Sitting on the porch practicing his

cursive “Aa”s, is a boy about the age of 7. The woman tells me this is her son,

and I can see the family resemblance, though she appears too old to be his

mother. Further confusion is brought on my head when I later ask Erasmos if he

has any children and he says “no”, yet the boy calls him “Papa”. On the other

hand, Erasmos is 70, or was that 60? I have trouble with those numbers.

Regardless, the kid is adorable and I instantly fall in love with him. He has

these big brown eyes and the cutest gapped-tooth smile. He also has no problems

coming up to me and talking, despite his limited Spanish.

The kids here are by far the happiest and seemingly

healthiest kids I have ever seen. They are able to play and scream and laugh

within the security that is this island neighborhood and family.

I give Erasmos my letter approving my project from the Guna

Congress and explain that I would like to introduce myself to the Sailar of

Tigre and to conduct a few interviews with whoever would be willing. He asks

how long I will be staying and is disappointed when I say that I will go back

to Nargana that evening if it is possible. He had apparently talked to

Iguayoikiler a few days before and was under the impression I would be staying

in Tigre. Not wishing to disappoint or offend, but only having packed my mummy sack

and a few necessities, I agree to stay one night.

We begin to walk. I am introduced to people in a manner I am

unable to catch their name and I am rarely told who they are in the community.

A couple times we walk into a seemingly random house to sit down. I am then

lead to realize that I am having an interview with an important person in the

community.

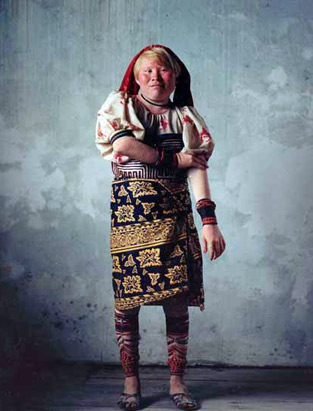

With Erasmos interpreting Guna into Spanish, I hold

interviews with the first Sailar and with a traditional healer who has albinism

himself. Both times beginning with

us merely walking into a house and him telling me to take a seat. The men

answer my questions briefly and frankly and we are done within a matter of

minutes. In terms of my research on albinism, my work is done on this island,

but I later come to learn that I have much more to learn from this community.

We continue on back to Erasmos’ house. We sit and talk.

Well, they talk mostly in Guna while I listen straining to recognize words. The

women work on molas, and Erasmos and I occasionally talk about politics, my

hometown, or other things. At some point I am told there is a dance that night

and I pray I don’t have to be a part of it. Dances were awkward enough in

gradeschool when I was just an inch or two too tall, here I would be a white whale

flopping amongst the normal fish. He gets up again, “Vamos” and we are headed

off. We end up back at his office. We do this several times throughout the day

and the next: sitting, talking, listening and walking whenever he tells me to.

Bathroom and shower also worked in a similar fashion. “Hay

baño” he shows me where the bathroom is. “Hay agua” – where and what to do with

the water are not as readily shown.

I am offered food and my U.S. self wants to politely refuse

being indebted further, but my Panamanian self has been lectured on the

rudeness of refusing offerings. Plus I had barely had much to eat that day,

being unsure of if I was supposed to feed myself, and I had no idea when I

would eat next. When given to me, I have no idea what the gray soup was before

I taste it, but courtesy and hunger out rule taste in these instances. (It

turned out that the yucca, lentil, plantain, chicken soup was good, and would

serve as one of few opportunities for hydration).

After another trip to and from the office, we sit in the

same manner until the sun goes down and the island glows with a few lights

powered by solar panels. At one point, our conversations are interrupted at

Erasmos’ home with the calls of “Suga! Suga! Suga!” I turn to see a huge, blue

suga coming toward my chair. After some frenzied running around and yelling of

directions, the blue crab is caught by one of the aunts, with two other people

corralling and one person on the flashlight. The crab was an escapee of one of

several barrels they have full to eat and sell.

Erasmos grabs a flashlight and says “vamos.” I, his

wife and “son” walk with him into the night. Maybe it’s just another walk, but

more likely I have the idea that we are headed toward that dance he mentioned

earlier.

I am relieved to find out that the dance is a performance

with no participation needed on my part except to watch. Men with flutes and

women with a maraca each play music and dance what I assume to be a fairly old

song and dance. Meanwhile others look on and women pass out candy and drink.

The occasion is a celebration for the completion of one year of one of the

leader of something…I think.

“Kelly, tomes?” …”uh si?” I drink yes, but what? I ask what

it is for fear it may be the infamous home-brew chicha. I am relieved to just

barely make out that it is only the corn meal drink we often have for breakfast

(brings back memories of my Ugandan home). We sit, drink, enjoy candy, and watch the performance. The

dancers are no professionals, but they all seem in good spirits, and missteps

and wrong turns are met with good-spirited laughter from participants and

audience members.

Erasmos tells me it is 9:30 and I only assume that means

time to vamos. We head back through the town of silhouetted huts, some beaming

with solar-powered light, against the backdrop of a star-filled sky.

I head to my room, my phone my only source of light. I am

thankful but wary of the mattress given to me and I am glad I thought to bring

my mummy sack. I tuck myself in

and listen to the surf as I think about and thank all those who have helped me

to get to where I am this very evening.